Bottom of the Well Theology

By Rev. Dr. Roman Soloviy

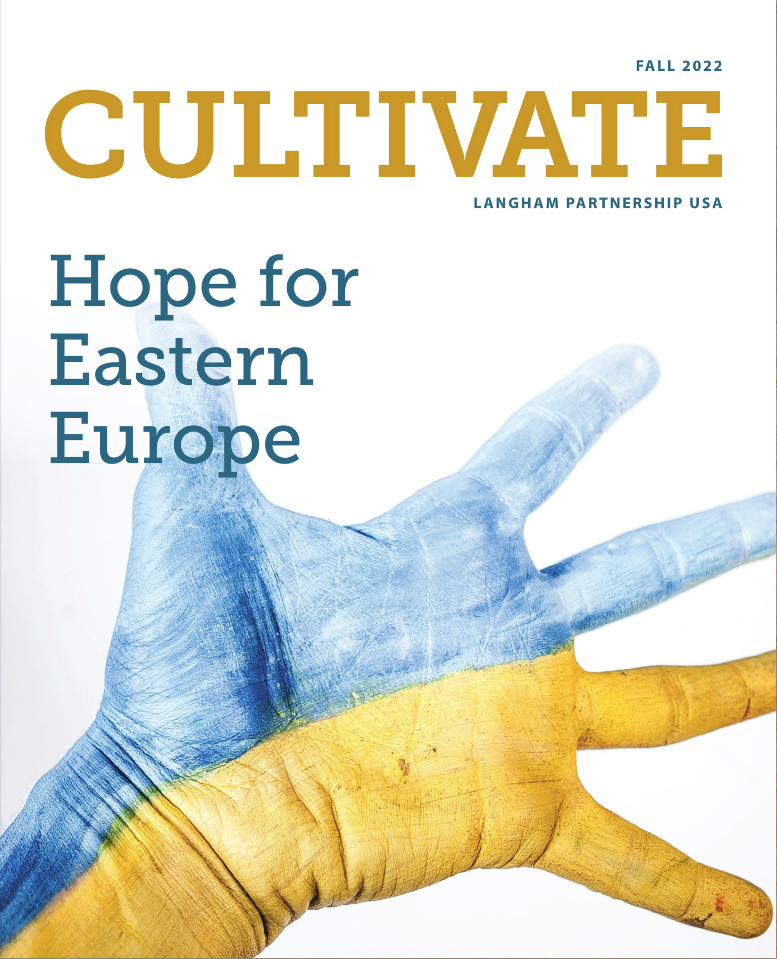

From Langham Partnership’s Fall 2022 Cultivate Newsletter

During this war, I have become increasingly aware of how emotional and geographic proximity relates to the perception of information. For our friends abroad, the news of the Ukrainian tragedy could remain just a piece of information about events in a neighboring country. For us, it is the destruction of our world, our families, and our futures. Even the most sympathetic cannot experience what we are experiencing here on an existential level. Peering into a well and being at the bottom of one are two completely different experiences!

- Who knows how to pray with a woman who was raped by a Russian soldier for a week and then watched him shoot her sick mother when the woman refused to go with him to Russia?

- What words can be said to the elderly residents of an assisted-living facility that was ruthlessly turned to rubble by a Russian tank?

- How does one comfort a wife whose husband ran to get help as she went into labor but was killed outside their house?

- How do we mourn over nameless civilians who have been tortured beyond recognition and even identification?

Theoretical answers I might have formulated prior to this war didn’t adequately prepare me for the actual words and deeds required in reality. So allow me to provide some Christian perspective from the bottom of the well—the most important lessons we, the Ukrainian Evangelical believers, have learned through facing the challenges brought by this war.

1. The Beauty of Solidarity. The vast majority of Ukrainian Christians have chosen “to share ill-treatment with the people of God rather than to enjoy the fleeting pleasures of sin” (Hebrews 11:25 NRSV). In times of great suffering, followers of the crucified Messiah cannot preach the gospel at a safe distance from a hellish reality. Those who haven’t seen sunlight for months, hiding in basements from Russian bombs and rockets; those who flee; those who seek healing for their physical and mental trauma; those who lost all they had built and their loved ones; and those who have been victims of physical violence do not need triumphant preaching or endless moralizing. They need Christ, who will drink with them the bitter cup of loneliness and abandonment and who will go with them all the way to the end. That is the Christ we try to preach and embody in acts of solidarity and self-denial, descending, as He does, to the last depths of human suffering.

For years, my colleague Anya P., a Ukrainian philosopher in Poland, has provided assistance to Ukrainian families with children who needed palliative care. Since the beginning of the war, she has been working hard to evacuate children from the fighting zone. Each evacuation requires coordinating many people, transport, funds, fuel, and so on. Together with my friends, we helped Anya through several complicated evacuations, each bearing witness to the incredible cooperation and beauty of solidarity. In one instance, evacuating an oxygen-dependent child from Kharkiv to Lviv (1017 km, 632mi) required special transport. Through social media and privately approached friends, we collected all the necessary funds for this evacuation within two hours!

There are different types of beauty. During these months of war, I have seen absolute beauty time and time again, the perfect incarnation of God’s love in our imperfect and war-torn world. I pray that this present experience of compassion and co-suffering in solidarity will open us up to the pain of other people, regardless of their location and circumstances, so that we would be distressed in their distresses (Isaiah 63:9 AMP) and bear their burdens as far as is possible (Galatians 6:2 ESV), showing forth the beauty of solidarity to the world.

2. The Need for Humility. I also pray that sharing our experience can foster humility in the church at large. From the very first days of the war, many of our international friends, surely with the best intentions, started to encourage Ukrainian Christians to forgive and reconcile with Russian Christians. Despite their orthodoxy and biblical vocabulary, I believe such appeals are terribly untimely. With the onset of the war, we in Ukraine have entered a Gethsemane, overwhelmed by loneliness and despair from the horror of the heinous violence suffered by innocent compatriots and friends and from the daily reports of the deaths of friends, colleagues, and co-laborers. Deathly sorrow overcomes hearts with the thought that the hardest times are still ahead. Although we certainly believe that after Calvary will come the Resurrection, for now, today, we are here in Gethsemane. The time came when the risen Jesus met with the apostles in Galilee and had a difficult conversation with Peter. He sent out His disciples to preach the gospel throughout the world, even to the oppressive Romans, at whose hands He had been crucified. But that was later. In the garden, His request was simple—to share His pain with Him, just to be near Him with no appeals and admonishments. That is the kind of humble solidarity we long for from the global church.

3. The Challenge of Truth. War from the thick of it and war from the news look different. Experiencing the war from the thick of it, you unconsciously strive for accurate wording. There is no “conflict in Ukraine,” not now and not in 2014-2015. Ukrainians are not at war with Ukrainians. There is no “special military operation,” as Russian propaganda calls this war. A war was started, armed and led by the Russian military and special services. And the purpose of this war is not some mythical “denazification”—unless by this notion one means the physical destruction of us, our culture, and our identity. Vague wording distorted by political correctness or propaganda is not only an epistemic fallacy but also an ethical mistake. Such word choice not only gives distorted information but also justifies and perpetuates the horrific injustice done to the victims of war.

Precise wording matters not just descriptively but also prescriptively. Abstract prayers for peace in Ukraine may suggest that Ukrainians must accept their fate of an “error of history” and return to the fold of the Russian empire. What is the way to real peace? We seek the peace that will allow us to remain free people with the right to choose our path. Therefore, to pray for peace in Ukraine and to be fair to Ukrainians means to pray for Russia’s military defeat and for the collapse of its economic power, which empowers this bloody war. Only if this happens can Russia agree to a peace deal which will not include the subjugation of Ukrainians.

To live through war is to experience anew the reality that truth is necessary and will set us free (John 8:32 ESV). It makes us long for the truth of the war to be known, and even more so for the sustained freedom to make the truth of Jesus known!

4. The Power of Hope. As some military experts predicted, the war is in a protracted phase with no reasonable expectations of cessation. For us in Ukraine, war is not a fragment of reality; it is the whole reality. It penetrates everywhere—determining the themes of our prayers and our perspectives on Scripture.

I used to wonder why many Holocaust survivors committed suicide later on—remembering poet Paul Celan, philosopher Jean Amery, and Primo Levy, grand witness to the horrors of Auschwitz (in which my own grandmother also died). But today, I understand that the level of violence and human evil they experienced deprived them of ways of returning to normal life, to healthy relationships, and the ability to trust people.

After the end of the war, one of the most difficult challenges for all of us will be to switch to peaceful life and return the war to its proper place – a fragment in the totality of our existence. For Christians, this liberation from the totality of war must begin now. How can this happen? It happens when we experience the hope that the infinite reality of the Kingdom of God inaugurated on the cross overcomes any totality on this side of eternity. I am very grateful to my friend, Pieter Kwant (Director of Langham Literature), who brought the attention of Ukrainian believers to this liberating truth at a recent seminar on the book of Revelation. All earthly totalities, even one as terrible and deadly as war, will one day give way to the infinite glory, peace, and love of the Kingdom of God. In prayer, in the Lord’s Supper, in the solidarity of the ecclesia, and in the beauty of sacrificial love, we experience the life of the age to come in which there will be no more death, no more tears, no more suffering. What a hope we have! That hope can get us through.

How we got here:

The last two centuries in Central and Eastern Europe saw empires collapse and modern nations emerge. The entire continent of Europe defeated the Nazi regime, enabling the western part of the continent to solidify its geopolitical unity. However, the alliance never extended eastward across the continent, leaving some nations under the influence of the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union collapsed, those nations gladly formed their own identities. However, post-Soviet Russia has proven to be no respecter of national boundaries and has advanced a new series of military conflicts to reclaim former Soviet territory. In 2014, Russia invaded Donetsk and Luhansk in Eastern Ukraine. In February 2022, that incursion turned into a full-scale war. Ukraine resists, asserting its unique identity and its desire to remain a self-determining state. But Russia’s aggression has led to the devastation of Ukraine’s cities, 1 brutal war crimes being investigated and documented by the UN2 , and the forced flight of 5.2 million Ukrainians, 3 leading to Europe’s largest refugee crisis since World War II.

Why it matters:

For the thirty years of Ukraine’s existence as a sovereign state, we neither took our statehood seriously nor made every effort to build it up. Frankly, not everything was great. But despite the problems, Ukraine remained a stronghold of freedom in the post-Soviet landscape. Here, anyone could practice their religion or none at all, read any book or nothing at all, hold various political views or be apolitical. This imperative of freedom at the metaphysical level has been woven into the genetic code of Ukrainian statehood. So the possible loss of freedom is what mobilizes the entire Ukrainian society today. And the Ukrainian Evangelical churches mirror the imperative for freedom. Having enjoyed some of the most favorable religious liberty laws since 1991, Ukraine hosts a large network of evangelical churches and theological schools, and Ukrainian missionaries serve in dozens of countries. The threat of losing religious freedom and returning to the Soviet totalitarian system motivates Ukrainians of all faiths to take all possible measures to help their country in these darkest days of our history.

1 Ruby Mellen, “Ukrainian Cities See Massive Destruction,” The Washington Post, 17 March 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/interactive/2022/ukraine-before -after-destruction-photos/.

2 Nell Clark, “What a U.N. Team Has Seen While Documenting Possible War Crimes in Ukraine,” NPR, 28 April 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/04/28/1095277848/ukrainerussia-war-crimes.

3 “Situation Ukraine Refugee Situation,” Operational Data Portal, 13 July 2022, https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine/location?secret=unhcrrestricted.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2022 issue of Cultivate—a free newsletter from Langham Partnership that features reflections from Majority World biblical leaders and stories of hope from the global church. Click here to read the full issue.

Roman Soloviy is the Director of the Eastern European Institute of Theology in Lviv, Ukraine. He also serves as editor-in-chief of Theological Reflections: Eastern European Journal of Theology, a chief editor of the book series “Contemporary Protestant Theology,” and a regional commissioning editor for Langham Literature.